Response of Leaves and Stem Leek (Allium porrum L.) Cultivars to Salt Stress on Growth, Yield, Mineral Composition, Organic and Antioxidant Compounds Cultivated in the Far North Region of Cameroon

1University of Maroua, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology Science, Po. BOX 46 Maroua, Cameroon

2University of Bamenda, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biological Sciences, P.O. BOX 39 Bambili, Cameroon

3University of Douala, Faculty of Science, Department of Botany, Po. Box 24157 Douala, Cameroon

4University of Yaoundé I, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology and Plant Physiology, Laboratory of Biotechnology and Environment, Unit of Physiology and Plant Improvement, Po. BOX 812 Yaoundé, Cameroon

Author and article information

Cite this as

Hand MJ, Ramza I, Nouck AE, Taffouo VD, Youmbi E. Response of Leaves and Stem Leek (Allium porrum L.) Cultivars to Salt Stress on Growth, Yield, Mineral Composition, Organic and Antioxidant Compounds Cultivated in the Far North Region of Cameroon. Plant Biotechnol Res. 2025; 2(1): 001-009. Available from: 10.17352/pbr.000003

Copyright License

© 2025 Hand MJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

Context: In the world, millions of hectares of cultivated land are affected by salt, making salinity a major constraint for plant production.

Objective: This investigation was conducted to examine the influence of salinity on plant growth, yield, and chemical compounds of leaves and stems of leek cultivars. Experiments are organized in a completely randomized block design with one plant per pot with as factors: two cultivars of leek and four levels of salinity (0, 60, 120, and 240 mM NaCl). The cultivars were well irrigated by fresh saline water for sixty days.

Results: This study demonstrated that increasing salinity reduces the morphological parameters, yield (to 30.43% in Gros long d’été and 30.78% in Monstreux conantan from control to 240 mM NaCl), ascorbic acid, and mineral distribution of the plant for all varieties. We notice that salinity increases osmolytes, antioxidant components, and Na content in the stem and leaves, with a larger accumulation in Gros long d’été than Monstreux conantan. The variety Gros long d’été has proven to be the most tolerant even in the presence of the highest concentration (240 mM NaCl).

Conclusion: Gros long d’été cultivar maintains great productiveness and nutritional quality in high levels of salinity; its salt-tolerance is higher than Monstreux conantan cultivar. The good behaviour of Gros long d’été cultivar facing salinity can be considered for its use to better enhance the Sahelian and coastal areas.

Abbreviations

ASA: Ascorbic Acid; Ca: Calcium; Cu: Copper; DW: Dry Weight; EC: Electric Conductivity; FC: Fiber Content; LFW: Leaf Fresh Weight; LRWC: Leaf Relative Water Content; Mg: Magnesium; N: Nitrogen; NL: Number of Leaves; C: Organic Carbon; P: Phosphorus; PH: Plant Height; K: Potassium; Na: Sodium; SP: Soluble Proteins; SD: Stem Diameter; SFW: Stem Fresh Weight; SRWC: Stem Relative Water Content; S: Sulfate; TFC: Total Flavonoids Content; TP: Total Phenolic; TSS: Total Soluble Sugar; WAS: Week After Sowing

Introduction

Leek (Allium porrum L.) is a plant having long leaves, more or less wide, opposed, planes, first gutter, then falling, pointed at the top, and jointly binding to the form to form a stem called “drump”, green, dark green, green-yellow, or bleed green. The white and soft leather of the leek was solely taken from several butting is the most consumed part. This one is pushed underground; the leek is classified as a root vegetable. Leek, rich in potassium and iron, can be consumed cooked or added to salads [1,2]. It has a wide spectrum of biological activities, priority due to the high antioxidant content [3], antimicrobial, cardio-protective, hypo-cholesterolemic, hypoglycemic, and anticancer activity [4]. Leek consumption is known to improve liver and gastrointestinal tract functioning, quicken metabolic processes, be useful in rheumatism treatment, decrease blood pressure, protect against anemia, enhance brain activity, inhibit platelet aggregation, and prevent neural tube defects [5]. In the case of leeks (Allium porrum L.), which have a shallow root system, with most roots concentrated in the uppermost 5–10 cm of soil and few extending beyond 30–40 cm, crops are particularly sensitive to salt stress; thus, salinity represents a significant input in terms of leek production and quality.

All over the globe, salt stress is considered one of the damaging abiotic stress factors affecting metabolism and plant production [6]. Increasing salinity has been considered a global threat to food security, causing significant conversion of agricultural arable land into unproductive wasteland. It affects mineral composition like N, P, K, S, and Ca, enzyme activity, photosynthesis, protein expression, and hormone metabolism [7]. Tolerance to salinity is a complex trait involving several physiological, biochemical, molecular, and gene networks [8]. Salinity disturbs the ionic balance, resulting in a reduction of water content, and oxidative damage due to accumulation of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to peroxidation of lipids [9]. It is essential to identify the physio-biochemical and molecular attributes for enhancing the salinity tolerance [8]. Salinity-induced increase in ROS results in oxidative damage to important molecules, including proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, etc. Increased ROS accumulation hampers redox homeostasis, declining the photosynthetic efficiency [10], nutrient and osmolyte metabolism [6]. It has been reported that plants displaying greater antioxidant and osmolyte metabolism, in addition to the selective accumulation of mineral ions, exhibit increased tolerance to salinity [7]. Increasing tolerance and fiber quality under salt-affected areas includes developing fiber crops for Na+ vacuolar sequestration and improvements in physio-biochemical attributes. High salt levels limit cellulose deposition, leading to weaker and less mature fiber [11]. The osmotic adjustment plays a vital role in the resistance or tolerance of the plant to stress [12]. The plant should synthesize organic solutes to adjust its water potential. Another strategy for salt entities is to synthesize osmoprotectors, mainly amino compounds and sugars, and accumulate them in the cytoplasm and organelles [13]. Coca, et al. [14] reported that the increased levels of NaCl concentration decreased growth, yield, and physiological parameters and increased osmolyte values. Leek plants are considered moderately sensitive to salinity, and their growth and yield can be significantly reduced at higher salt concentrations [15].

The objective of this study is to determine the effect of different levels of salinity on the agromorphological, physiological, and nutritional quality of leek. It is determining the relative level of tolerance or resistance to the salinity of two leek cultivars produced in the Sahelian region of Cameroon.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

This experiment is carried on from 26 June 2023 to 30 October 2023 at Palar harde, in the Maroua city, Department of Diamare, Region of Far Nord of Cameroun (latitude: 10°36’37,57’’N, longitude: 14°17’34,41’’ E). The climate is tropical of a hot sudano-sahelian type, with average annual rainfall estimated at 700 mm from June to September. Temperatures range from 25 °C à 30 °C in the rainy season and culminate at 45 °C in the dry season. Land is mainly the sandlike-clay type. These periods of heapers are a consequence of precipitation related to an important evaporation, thus promoting the accumulation of salt in the soil [16].

Plant growth conditions and treatment

The experiments are organized like a completely randomized block and three replicates (let 03 leek plants per replication) per treatment with as factors: two cultivars of leek (‘Gros long d’été’ and ‘Monstreux de conatant’) and four levels of salinity (0, 60, 120, and 240 mM NaCl). Pot experiments were carried out with leek cultivars. Seeds were provided by the breeding program of the TECHNISEM (SEMAGRI, Maroua). Ten kilograms of the sieved soil was weighed into pots, each of seven litres capacity, perforated at the bottom to allow unimpeded drainage.

The bare-root transplants of varieties with 4.5 to 7 mm thick stems were produced in nursery beds. In July 2023, leeks were manually transplanted into a plant bed that was cultivated on the previous day, using a rotary cultivator. Before transplanting roots and leaves of the transplants were trimmed according to standard practice. The planting depth of transplants was 6 cm. Inter-row spacing was 45 cm, whereas in-row spacing was 15 cm to give a population of 222,000 plants ha-1. Before initiating treatments, plants were irrigated with normal tap water using a hand sprinkler to full saturation for two weeks in order to improve root development [17]. After which, 500 ml of water was applied to each pot, and this was able to wet the soil to full saturation. All plants were fertilized daily with a Hoagland solution [18]. The amendment in each case was applied 5 WAS with 5 t ha-1 of organic fertilizer. The pH of the nutrient solution was adjusted to 7.0 by adding HNO3 0.1 mM. Neem oil (insecticide) at 5 ml/g per 1 liter of water and Azadirachtine (fungicide) at 2.5 g per hectare were applied as pre-emergence weed control measures, and supplementary hoe-weeding was done at 8 and 11 WAS.

Soil moisture content determination, irrigation water, and analysis

Soil samples were collected from representative spots on the experimental site, from where soil was collected for potting using a soil auger to a depth of 20 cm, and the samples were made into a sample. A sub-sample was taken, air-dried, crushed, and sieved with a 2-mm mesh sieve, after which physical and chemical analyses were carried out (Table 1). The following chemical analyses were done on the soil and tap water (Tables 1,2). Organic carbon (C) was determined by the wet oxidation procedure [19] and total Nitrogen (N) by the micro-Kjeldahl digestion method. Magnesium (Mg) was extracted using the Mehlich 3 method and determined by Auto Analyzer 5Technicon 2). The total and available soil phosphorus (P) were determined by the method of Okalebo, et al. [20]. Soil was measured potentiometrically in a 1:2.5 soil: water mixture. Calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and sodium (Na) were determined by a flame photometer (JENWAY) as described by Taffouo, et al. [21]. Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, HCO3-, SO42-, NO3, Cl- content in the water tap was determined by using the colorimetric amperometric titration method [22] (Table 2). Electric conductivity and pH were determined by a conductometer.

Plant growth and yield parameters

Seedlings were harvested by carefully removing and washing the soil particles from the roots, after which the plant parts were separated into shoots and roots [23]. Tissues (leave and stem) were dried for 24 h at 105 ˚C [24]. The dry samples were weighed. Plant samples were harvested after 16 weeks of culture and under 10 weeks of salt stress. Plants were collected to determine agro-morphological characters (number of leaves per plant, plant height, fresh leaf weight, stem fresh weight, stem diameter, and yield) of leek.

The relative water content (RWC) in leaf and stem was recorded according to the formula as follows: RWC = (FFW - FDW)/ (TW - FDW) × 100, where FFW is fresh weight, FDW is dry weight, and TW is turgid weight [25].

Osmolyte contents

For measurement of total soluble sugar (TSS), a modified phenolsulfuric assay was used [26]. Subsamples (100 mg) of dry leaves and stems were placed in 50 mL centrifuge tubes. 20 mL of extracting solution (glacial acetic acid: methanol: water, 1:4:15 (v/v/v)) was added to the ground tissue and homogenized for 15 sec at 16000 rpm. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was decanted into a 125 ml Erlenmeyer flask. The residue was resuspended in 20 mL of the extracting solution and centrifuged for another 5 min. The supernatant was decanted, combined with the original extract, and made up to 100 mL with water. One mL of 5% (v/v) phenol solution and 5 mL of concentrated H2SO4 were added to 1 mL aliquots of SS (reconstituted with 1 mL water). The mixture was shaken, cooled to room temperature, and the absorbance was recorded at 490 nm wavelength with a spectrophotometer (Pharmaspec UV-1700 model). The amount of SS present in the extract was calculated using a standard curve prepared from a graded concentration of glucose.

Soluble protein content (SP) was determined by [27] method. Briefly, an appropriate volume (from 0 - 100 µl) of the sample was aliquoted into a tube, and the total volume was adjusted to 100 µl with distilled water. 1 mL of Bradford working solution was added to each sample well. Then the mixture was thoroughly mixed by a vortex mixer. After leaving for 2 min, the absorbance was read at 595 nm. The standard curve was established by replacing the sample portions in the tubes with proper serial dilutions of bovine serum albumin.

Proline content (PRO) was estimated using Bates’ [28] method. 0.5 g of fresh leaves and stems was weighed and put inside a flask. 10 mL of 3% aqueous sulphosalicylic acid was poured into the same flask. The mixture was homogenized and then filtered with a Whatman No. 1 filter paper. 2 mL of filtered solution was poured into a test tube, and then 2 mL of glacial acetic acid and ninhydrin were added to the same tube. The test tube was heated in a warm bath for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by placing the test tube in an ice bath. 4 mL of toluene was added to the test tube and stirred. The toluene layer was separated at room temperature, the mixture purple color, and the absorbance of the purple mixture was read at 520 nm by a UV spectrophotometer (Pharmaspec model UV-1700). At 520 nm, the absorbance was recorded, and the concentration of PRO was determined using a standard curve as mg/g FW.

Fiber content (FC) analysis has been realized by the method of Van Soest [29].

Antioxidant levels

For estimation of ascorbic acid content (ASA), 1 g of frozen leaf and stem tissues was homogenised in 5 mL of ice-cold 6% m-phosphoric acid (pH 2.8) containing 1 mM EDTA [30]. The homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4˚C. The supernatant was filtered through a 30-µm syringe filter, and 50 µL of the filtrate was analyzed using an HPLC system (PerkinElmer series 200 LC and UV/VIS detector 200 LC, USA) equipped with a 5-µm column (Spheri-5 RP-18; 220 × 4.6 mm; Brownlee) and UV detection at 245 nm with 1.0 mL/min water (pH: 2.2) as the mobile phase, run isocratically [31].

Total phenolic content of extracts from cultured sprouts of Garden cress exposed to different levels of PEG, Mannitol, and NaCl was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu micro method [32]. A 20 μl aliquot of extract solution was mixed with 1.16 ml of distilled water and 100 μl of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, followed by 300 μL of 200 g L-1 Na2CO3 solution. The mixture was incubated in a shaking incubator at 40 °C for 30 min, and its absorbance at 760 nm was measured. Gallic acid was used as a standard for the calibration curve. Total phenolic contents were expressed as gallic acid (mg gallic acid g-1 dry weight).

Total flavonoid content of extracts from cultured sprouts of Garden cress with different levels of PEG, mannitol, and NaCl was determined by the method of Ordon, et al. [33]. A 0.5 ml aliquot of 20 g L-1 AlCl3 ethanolic solution was added to 0.5 ml of extract solution. After 1 h at room temperature, the absorbance at 240 nm was measured. A yellow color indicated the presence of flavonoids. Extract samples were evaluated at a final concentration of 0.1 mg ml-1. Total flavonoid content expressed as QE (mg QE g-1 dry weight).

Nutrient content

Ca, K, Mg, and P contents in the leaf and stem tissue of the plants were evaluated in dry, ground, and digested samples in a CEM microwave oven [34]. P was determined by colorimetry; potassium by flame photometry; calcium and magnesium by atomic absorption spectrometry [35]. Iron and Cu content were determined by the method reported in [36]. Leaf and stem of leek were dry ashed at 450˚C for 2 hours and digested in a heat cave with 10 ml HNO3 1 M. The solution was filtered and adjusted to 100 ml with HNO3 at 1/100 and analyzed with an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Rayleigh, WFX-100).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was conducted as a factorial completely randomized design with four NaCl treatments (0, 60, 120, 240 mM NaCl) and two cultivars in four replications. Data are presented in terms of mean (±standard deviation). All data were statistically analysed using Statistica (version 9, Tulsa, OK, USA) and first subjected to analyses of variance (ANOVA). Statistical differences between treatment means were established using the Fisher LSD test at p < 0.05.

Results

Effect of salinity on leek growth, yield, and physiological parameters

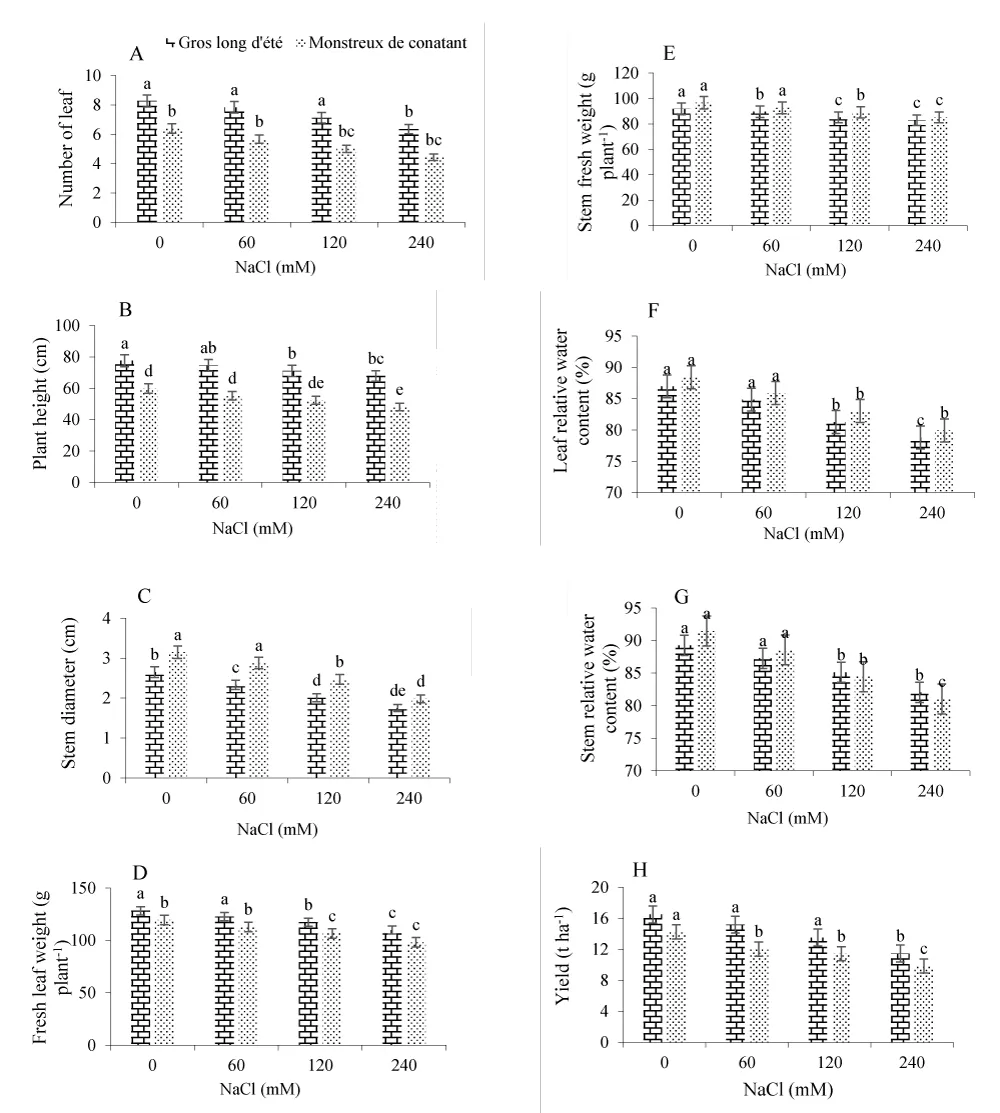

The significant differences are observed in Gros long d’été and Monstreux canantan varieties for all salt stress levels, plant growth, and yield parameters (Figure 1). PH and NL per plant ranged between 74.62 cm for Gros long d’été and 55.21 cm for Monstreux canantan (at 60 mM NaCl) to 67.84 cm for Gros long d’été and 48.05 cm for Monstreux canantan (at 240 mM NaCl); 7.84 for Gros long d’été and 5.67 for Monstreux canantan (60 mM NaCl) to 6.35 for Gros long d’été and 4.43 for Monstreux canantan (at 240 mM NaCl), respectively. The thickest stem diameter values (2.65 cm for Gros long d’été and 3.15 cm for Monstreux canantan) were obtained for the control treatment, and the thinnest (1.75 cm for Gros long d’été and 1.98 cm for Monstreux canantan) were obtained for the 240 mM NaCl treatment.

The yield of leek varied among treatments, decreasing with increases in NaCl rates (Figure 1H). Salt stress in the 60, 120, and 240 mM NaCl treatments resulted in decreases in yield of 7.81%, 19.92% and 30.40% for Gros long d’été and 15.53%, 19.71% and 30.80% for Monstreux canantan, respectively, in comparison to the control (0 mM NaCl). Leaf and stem fresh weight, which are the main factors in leek yields, also varied, from a high for Gros long d’été (128.25 and 91.82 g/plant, respectively) and Monstreux canantan (119.48 and 96.63 g/plant, respectively) at 0 mM NaCl; to a low for Gros long d’été (109.89 and 82.92 g/plant, respectively) and Monstreux canantan (98.08 and 85.11 g/plant, respectively) at 240 mM NaCl respectively (Figure 1D and 1E).

Relative water content of leaf and stem was significantly affected by salinity, with highest LRWC value (86.96% for Gros long d’été and 88.43% for Monstreux canantan) and SRWC (89.25% for Gros long d’été and 91.47 % for Monstreux canantan) obtained with the control (0 mM NaCl) treatment and the lowest LRWC value (78.81% for Gros long d’été and 82.03 % for Monstreux canantan) and SRWC (79.94% for Gros long d’été and 81.02 % for Monstreux canantan) with the 240 mM NaCl treatment (Figure 1F and 1G).

Effect of NaCl on leaf and stem nutritional value

The results obtained in Table 3 show an increase in soluble sugars, fiber, and protein content in stressed plants with respect to the control. The highest SP, TSS, FC, and PRO levels were recorded at the level of plants subjected to severe stress. This increase varied from 0 to 240 mM NaCl in the leaf of Gros long d’été (89.98, 31.98, 33.91, and 28.07 % respectively), the stem of Gros long d’été (102.48, 47.49, 40.11, and 18.49 % respectively), in leaf of Monstreux conantan (106.46, 41.93, 72.17, and 37.07% respectively) and stem of Monstreux conantan (106.49, 56.59, 40.11 and 22.41 % respectively).

The Gros long d’été and Monstreux canantan varieties differed significantly for total polyphenols, total flavonoid content, and ascorbic acid in response to salinity (p < 0.05) (Table 3). The highest content of TP and TFC was observed on the leaf of Gros long d’été (20.14 mg GAE g-1 and 0.87 mg CE g-1), the stem of Gros long d’été (15.92 mg GAE g-1 and 0.75 mg CE g-1), the leaf of Monstreux canantan (18.58 mg GAE g-1 and 0.86 mg CE g-1), and the stem of Monstreux canantan (16.36 mg GAE g-1 and 0.72 mg CE g-1, respectively) at 240 mM NaCl. Contrary, ASA decreased under salinity conditions. The low ASA content was obtained from the leaf (7.88 mg g-1) and stem (9.55 mg g-1) of Gros long d’été and leaf (6.98 mg g-1) and stem (7.69 mg g-1) of Monstreux canantan at 240 mM NaCl (Table 3).

Salinity elevated the Na and reduced the Ca, K, Cu, Fe, and Mg content in the leaves and stems of all leek cultivars (Table 4). The greatest Na is obtained at 240 mM NaCl for leaf (0.46 mg g-1) and stem (0.51 mg g-1) of Gros long d’été and leaf (0.45 mg g-1) and stem (0.55 mg g-1) of Monstreux canantan. However, high content of Mg, K, Cu, Fe and Ca are observed at the control (0 mM NaCl) for Gros long d’été (0.76 mg g-1, 18.44 mg g-1, 1.48 mg kg-1, 135.45 mg kg-1, 4.72 mg g-1 in leaf and 0.79 mg g-1, 24.26 mg g-1, 1.93 mg kg-1, 210.85 mg kg-1, 5.51 mg g-1 in stem respectively) and Monstreux canantan (0.70 mg g-1, 17.96 mg g-1, 0.98 mg kg-1, 138.56 mg kg-1, 5.16 mg g-1 in leaf and 0.76 mg g-1, 19.75 mg g-1, 0.73 mg kg-1, 208.82 mg kg-1, 5.38 mg g-1 in stem respectively) and the lowest content obtained at 240 mM NaCl.

Discussion

Effect of salinity on leek growth, yield, and physiological parameters

Significant differences were found in PH, SD, and NL between the 60, 120, and 240 mM NaCl. Reductions of PH, SD, and NL can be assigned to a decrease in cell extension due to salt. These results are similar to those obtained by Ashraf and Orooj [37] and Rebey, et al. [38], who showed that the reduction of biomass caus2ed by salt stress in Trachyspermum ammi [L.] Sprague and Cuminum cyminum L., respectively. This decrease effect was probably due to the impact of salt on the stomata and photosynthesis process, as intercellular CO2 concentration was reduced and photosynthetic enzymes, chlorophylls, and carotenoids were disturbed, respectively [39].

This implied that increasing of saline level may improve leek yield. Over-saline stress (240 mM NaCl) caused a greater reduction in vegetative growth with lower plant heights, number of leaves, and thinner stem diameters, resulting in less productive stem and leave fresh weight as compared to the other treatments. Kiremit and Arslan [40] reported 1.21 dSm-1 to be the threshold value for leek, indicating leek crops to be moderately sensitive to soil salinity. Therefore, soil salinity under deficit irrigation needs to be taken into consideration to prevent harmful levels of salt from accumulating in the soil profile, which can lead to reductions in plant growth and productivity.

A decrease in RWC in plants under saline conditions has been observed in many plants and may depend on plant vigor. Likely, in this constraint, the ability to achieve good osmoregulation and to preserve cell turgor is reduced [41]. It seems that the concentration of organic solutes to maintain the membrane is not sufficient in this case [42,43]. Decreases in leaf area and stem diameters probably appear due to the fact that salt stress hurts plant cell growth and division due to turgor loss in expanded cells. Reductions in leaf growth rates can be attributed to premature leaf senescence and defoliation accelerated due to limited crop water uptake by roots, as reported in the work of Passioura and Angus [44].

Effect of NaCl on leaf and stem nutritional value

Osmotic adjustment is mediated by the accumulation of osmolytes (amino acids, proline, sugars, and proteins) in plant cells under salt stress. Increased accumulation of osmolytes helps plants lower their water potential to facilitate water uptake from saline soils [45,46]. Several authors designed sugar and proteins, such as great osmo-regulators, which can have an important role in the osmotic adjustment and adaptation of plants for osmotic stress [47]. Soluble sugars protect the membranes against dehydration, and they participate largely in the lowering of osmotic potential in wheat. Stressed plants reacted by increasing quantities of soluble sugars and proteins in their cells [48]. Sarker [11] reported that fiber has a significant role in palatability, digestibility, and the remedy of constipation. Organic osmolytes are synthesized and accumulated in varying amounts amongst different plant species to adjust osmotic potentials and protect cells.

This study revealed that ASA in the stem and leaf of all leek cultivars decreased with salt concentration. Ascorbic acid is an essential nutrient that occurs widely in crop food products, especially in fresh fruits and green leafy vegetables [49]. Beltagi [9] reported that ascorbic acid is a small, water-soluble antioxidant molecule that acts as a primary substrate in the cyclic pathway of enzymatic detoxification of hydrogen peroxide. Under salinity stress, Alam, et al. [50] observed an increase in the flavonoid content in Portulaca oleracea. Yarnia, et al. [51] report that the phenolic compounds in amaranth increase with increasing salt stress. Salt stress, which enhances the accretion of the greater phenolic and flavonoid compounds within the plant cell, may accelerate the capacity of the plant to cope with oxidative stress under excessive salt concentrations or adverse conditions [52].

The concentrations of all measured nutrients (Fe, Cu, K, Mg, and Ca) in the roots and shoots declined under salinity. Benito, et al. [53] reported that the reduction of these minerals may be directly linked to excessive Na+ absorption by the roots. It is well established that salt stress affects growth in plants in three ways: through osmotic effects, through the specific toxicity of the saline ions, and or through nutritional disturbances [54]. High levels of Na+ decrease the availability of other ions such as K+, Ca++, Mg++, Cu++, and Fe++ due to the cation competition, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies [55]. Increased Na+ concentration usually results the competition with K+, Ca++, Mg++, Cu and Fe) for enzymes that require these ions, a decrease in K+, Ca++, Mg++, and it may be critical for tolerance to maintain cytosolic K+, Ca++, Mg++, Cu++, Fe++ levels at an acceptable level or to maintain homeostasis [56]. The toxic effect sensitivity or tolerance to salinity varies by species and varieties [57-60].

Conclusion

The present study showed saline rates to have a significant effect on the growth, yield, nutrient composition, antioxidant, and osmolytes of Gros long d’été and Monstreux conantan cultivars. The increasing level of NaCl decreased growth, yield, ascorbic acid, and relative water content of leaves and stems. Salt stress had a significant effect on the accumulation of osmolytes, fiber, and total phenolic content. All the same, Gros long d’été cultivar showed more tolerance with the higher salinity (240 mM NaCl) than Monstreux conantan. Therefore, we recommended that the Gros long d’été cultivar could be cultivated under a higher NaCl stress condition for NaCl recycling, while Monstreux conantan cultivar should be under a lower NaCl stress. Furthermore, Gros long d’été cultivar, which is cultivated under salinity stress, could contribute to the high quality of the final product.

Future research studies may explore molecular mechanisms and the underlying genetics of salinity tolerance, and embracing conventional breeding approaches, along with emerging breeding tools, can help improve genetic gain under salinity stress, leading to more resilient crops for the future.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all who helped us carry out this study. This work is not funded.

Author contributions

Mathias Julien Hand: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Imael Ramza: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft

Alphonse Ervé Nouck: Formal Analysis, Resources, Visualization

Victor Désiré Taffouo: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization

Emmanuel Youmbi: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization

References

- Theunissen J, Schelling G. Infestation of leek by thrips tabaci as related to spatial and temporal patterns of undersowing. Bio Control. 1998;43(1):107-11. Available from: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/infestation-of-leek-by-thrips-tabaci-thysanoptera-thripidae-as-re/

- Koca I, Tasci B. Mineral composition of leek. Acta Hortic. 2016;1143:147-151. Available from: https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1143.21

- Ben Arfa A, Najjaa H, Yahia B, Tlig A, Neffati M. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic composition as a function of genetic diversity of wild Tunisian leek (Allium ampeloprasum L.). Acad J Biotechnol. 2015;3:15-26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.15413/AJB.2015.0121

- Radovanović B, Mladenović J, Radovanović A, Pavlović R, Nikolić V. Phenolic composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Allium porrum L. (Serbia) extracts. J Food Nutr Res. 2015;3:564-569. Available from: https://pubs.sciepub.com/jfnr/3/9/1/index.html

- Fattorusso E, Lanzotti V, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Cicala C. The flavonoids of leek, Allium porrum. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:565-569. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00039-5

- Ahanger MA, Agarwal RM. Salinity stress-induced alterations in antioxidant metabolism and nitrogen assimilation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L) as influenced by potassium supplementation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;115:449-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.04.017

- Ahmad P, Ahanger MA, Alam P, Alyemeni MN, Wijaya L, Ali S, Ashraf M. Silicon (Si) supplementation alleviates NaCl toxicity in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) wilczek] through the modifications of physio-biochemical attributes and key antioxidant enzymes. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38(1):70-82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-018-9810-2

- Gupta B, Huang B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Int J Genomics. 2014;2014:701596. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/701596

- Beltagi MS. Exogenous ascorbic acid (vitamin C) induced anabolic changes for salt tolerance in chick pea (Cicer arietinum L.) plants. African Journal of Plant Science. 2008;2(10):118-123. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228661116_Exogenous_ascorbic_acid_vitamin_C_induced_anabolic_changes_for_salt_tolerance_in_chick_pea_Cicer_arietinum_L_plants

- Khan MIR, Asgher M, Khan NA. Alleviation of salt-induced photosynthesis and growth inhibition by salicylic acid involves glycine betaine and ethylene in mungbean (Vigna radiata L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;80:67–74. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.03.026

- Sarker U, Islam MT, Rabbani MG, Oba S. Genetic variation and interrelationship among antioxidant, quality, and agronomic traits in vegetable amaranth. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2016;40:526–535. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3906/tar-1601-24

- Munns R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:239–250. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00808.x

- Chen H, Jiang JG. Osmotic adjustment and plant adaptation to environmental changes related to drought and salinity. Environ Rev. 2010;18:309–319. Available from: https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/A10-014

- Coca CA. NaCl effects on growth, yield, and quality parameters in onion (Allium cepa L.) under controlled conditions. Rev Colomb Cienc Hortic. 2012.

- Ayers RS, Westcot. Water quality for agriculture. Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 29. 1989. Available from: https://www.fao.org/4/t0234e/t0234e00.htm

- Munns RA, James A, Lauchli. Approaches to increasing the salt tolerance of wheat and other cereals. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(5):1025‐1043. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj100

- Imana C, Aguyoh JN, Opiyo A. Growth and physiological changes of tomato as influenced by soil moisture levels. Second RUFORUM Biennial Meeting; Entebbe, Uganda. 2010. Available from: http://repository.ruforum.org/system/tdf/Imana.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=34720&force=

- Hoagland DR, Arnon DI. The water culture method for growing plants without soil. University of California, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station. 1950. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1850958

- Walkley A, Black IA. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934;37:29–38. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003

- Okalebo JR, Gathua WK, Woomer PL. Laboratory methods of soil and plant analysis: a working manual. Soil Biology and Fertility, Soil Science Society of East Africa, Kari, UNESCO-ROSTA; Nairobi, Kenya. 1993;88. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2505600

- Taffouo VD, Djiotie NL, Kenne M, Din N, Priso JR, Dibong S, Akoa A. Effect of salt stress on physiological and agronomic characteristics of three tropical cucurbit species. Journal of Applied Bioscience. 2008;10:434–441. Available from: https://www.m.elewa.org/JABS/2008/10(1)/2.pdf

- Taleisnik E, Peyrano G, Arias C. Response of Chloris gayana cultivars to salinity. 1. Germination and early vegetative growth. Trop Grassl. 1997;31:232–240. Available from: https://www.tropicalgrasslands.info/public/journals/4/Historic/Tropical%20Grasslands%20Journal%20archive/PDFs/Vol_31_1997/Vol_31_03_97_pp232_240.pdf

- Metwally SA, Khalid KA, Abou-Leila BH. Effect of water regime on the growth, flower yield, essential oil, and proline contents of Calendula officinalis. Nusantara Bioscience. 2013;5(2):65-69. Available from: https://smujo.id/nb/article/view/902

- Taffouo VD, Kouamou JK, Ngalangue LMT, Ndjeudji BAN, Amougou A. Effect of salinity stress on growth, ion partitioning and yield of some cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) cultivars. International Journal of Botany. 2009;5(2):135-145. Available from: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=ijb.2009.135.143

- Sánchez FJ, De Andrés EF, Tenorio JL, Ayerbe L. Growth of epicotyls, turgor maintenance and osmotic adjustment in pea plants (Pisum sativum L.) subjected to water stress. Field Crops Research. 2004;86:81-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00121-7

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry. 1956;28:350-356. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ac60111a017

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248-254. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

- Bates L, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant and Soil. 1973;39(2):205-207. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00018060

- Van Soest PJ. Use of detergents in the analysis of fibrous feeds. Preparation of fiber residues of low nitrogen content. Journal of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists. 1963;46:825-829. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1840997

- Gossett DR, Millhollon EP, Lucas MC. Antioxidant response to NaCl stress in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive cultivars of cotton. Crop Science. 1994;34:706-714. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1994.0011183X003400030020x

- Gahler S, Otto K, Bohm V. Alterations of vitamin C, total phenolics, and antioxidant capacity as affected by processing tomatoes to different products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51:7962-7968. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/jf034743q

- Saeedeh A, Asna U. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of mulberry (Morus indica L.) leaves. Food Chemistry. 2007;102:1233-1240. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.013

- Ordon JD, Gomez MA, Vattuone MI. Antioxidant activities of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz extracts. Food Chemistry. 2006;97:452-458. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.024

- Abreu CA. Comparison of analytical methods for evaluating metal availability in soils. Brazilian Journal of Soil Science. 1995;19:463-468.

- Malavolta E, Vitti GC, Oliveira SA. Avaliação do estado nutricional das plantas: princípios e aplicações. 2nd ed. Piracicaba (SP): POTAFOS; 1997;319. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2937675

- Pauwels JM, Van Ranst E, Verloo M, Mvondo ZA. Analysis methods of major plant elements. In: Pedology Laboratory Manual: Methods of Plants and Soil Analysis. Publica Agricol; 1992;28. Brussels. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2937676

- Ashraf M, Orooj A. Salt stress effects on growth, ion accumulation, and seed oil concentration in an arid zone traditional medicinal plant, ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi [L.] Sprague). J Arid Environ. 2006;64:209–220. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.04.015

- Rebey IB, Bourgou S, Rahali FZ, Msaada K, Ksouri R, Marzouk B. Relation between salt tolerance and biochemical changes in cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) seeds. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:391–402. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2016.10.001

- Taârit MB, Msaada K, Hosni K, Marzouk B. Physiological changes, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Salvia officinalis L. grown under saline conditions. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:1614–1619. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4746

- Kiremit MS, Arslan H. Effects of irrigation water salinity on drainage water salinity, evapotranspiration, and other leek (Allium porrum L.) plant parameters. Scientia Horticulturae. 2016;201:211–217. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.02.001

- El Jaafari S. Durum wheat breeding for abiotic stress resistance: defining physiological traits and criteria. In: Royo C, Nachit M, Di Fonzo N, Araus JL, editors. Durum wheat improvement in the Mediterranean region: new challenges. Zaragoza: CIHEAM; 2000;251–256. (Options Méditerranéennes: Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; 40). Available from: https://om.ciheam.org/om/pdf/a40/00600038.pdf

- Karimpour M. Effect of drought stress on RWC and chlorophyll content on wheat (Triticum durum L.) genotypes. World Ess J. 2019;7:52–56.

- Ilyas M, Mohammad N, Nadeem K, Ali H, Aamir HK, Kashif H, et al. Drought tolerance strategies in plants: a mechanistic approach. J Plant Growth Regul. 2020. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00344-020-10174-5

- Passioura JB, Angus JF. Improving productivity of crops in water-limited environments. Adv Agron. 2010;106:37–75. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(10)06002-5

- Munns R, Passioura JB, Colmer TD, Byrt CS. Osmotic adjustment and energy limitations to plant growth in saline soil. New Phytol. 2020;225:1096. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15862

- Zhao S, Zhang Q, Liu M, Zhou H, Ma C, Wang P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4609. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8125386/

- Bouatrous Y. Water stress correlated with senescence in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf). Adv Environ Biol. 2013;7(7):1306–1314. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259007817_Water_stress_correlated_with_senescence_in_durum_wheat_Triticum_durum_Desf

- Hireche R. Response of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) to water stress and the depth of the seedlings. Magister Thesis. Univ. EL Hadj Lakhdar, Batna. 2006;83.

- Ratnakar A, Rai A. Effect of NaCl salinity on β-carotene, thiamine, riboflavin, and ascorbic acid contents in the leaves of Amaranthus polygamous L. var. Pusa Kirti. Journal of Stress Physiology & Biochemistry. 2013;9:187–192. Available from: https://sciencebeingjournal.com/sites/default/files/Effect%20of%20NaCl%20salinity%20on%20%CE%B2-carotene,%20thiamine,%20riboflavin.pdf

- Alam MA, Juraimi AS, Rafii MY, Hamid AA, Aslani F, Alam MZ. Effects of salinity and salinity-induced augmented bioactive compounds in purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) for possible economic use. Food Chem. 2015;169:439–447. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.019

- Yarnia M, Benam MBK, Nobari N. The evaluation of grain and oil production, some physiological and morphological traits of amaranth cv. Koniz as influenced by the salt stress in hydroponic conditions. J Agric Food Environ Sci. 2016;69:87–93. Available from: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122550/records/68b6dbf868d9e6806700a86a

- Turkan I, Demiral T. Recent developments in understanding salinity tolerance. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;67:2–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.05.008

- Benito B, Haro R, Amtmann A, Cuin TA, Dreyer I. The twins K+ and Na+ in plants. J Plant Physiol. 2014;171:723–731. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2013.10.014

- Odjegba VJ, Chukwunwike IC. Physiological responses of Amaranthus hybridus L. under salinity stress. Indian Journal of Innovations and Developments. 2012;1(10):742–748.

- Atta K, Pal AK, Jana K. Effect of salinity, drought, and heavy metal stress during the seed germination stage in ricebean (Vigna umbellata (Thunb.) Ohwi and Ohashi). Plant Physiol Rep. 2021;26:109–115. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40502-020-00542-4

- Shabala S, Pottosin I. Regulation of potassium transport in plants under hostile conditions: implications for abiotic and biotic stress tolerance. Physiologia Plantarum. 2014;151:257–279. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12165

- El Midaoui M, Benbella M, Aït Houssa A, Ibriz M, Talouizte A. Contribution to the study of some salinity adaptation mechanisms in cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Revue THE. 2007;(136):29–34.

- Fatma M, Masood A, Per TS, Khan NA. Nitric oxide alleviates salt stress-inhibited photosynthetic performance by interacting with sulfur assimilation in mustard. Front Plant Sci. 2016;25:521. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2016.00521/full

- Hand MJ, Taffouo VD, Nouck AE, Nyemene KPJ, Tonfack LB, Meguekam TL, Youmbi E. Effects of salt stress on plant growth, nutrient partitioning, chlorophyll content, leaf relative water content, accumulation of osmolytes and antioxidant compounds in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivars. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2017;45(2):481–490. Available from: https://www.notulaebotanicae.ro/index.php/nbha/article/view/10928

- Nouck AE, Hand MJ, Numfor EN, Ekwel SS, Ndouma CM, Shang EW, Taffouo VD. Growth, mineral uptake, chlorophyll content, biochemical constituents and non-enzymatic antioxidant compounds of white pepper (Piper nigrum L.) grown under saline conditions. Int J Biol Chem Sci. 2021;15(4):1457–1468.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley